This project was originally started as part of the i3 Detroit OpenAccess control system for RFID entry. I promise I’ll write an entry on that soon, but I’ve got to shake down all the bugs first. These displays that I got to play with are specifically 1080-s4-13-x-x, which according to the manual means that our displays have four lines of twenty 5mm characters each, 2-RS485 serial ports, 13 buttons, no memory, and no clock. Because these are the only two displays I have, theirs are the only features I implemented.

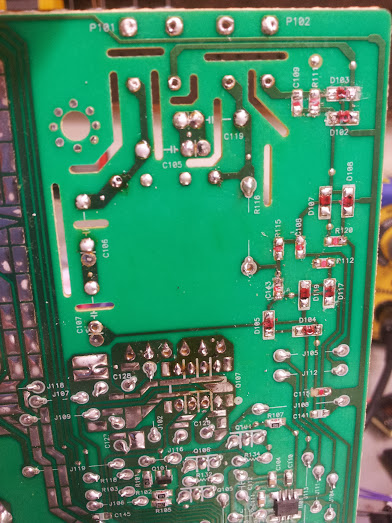

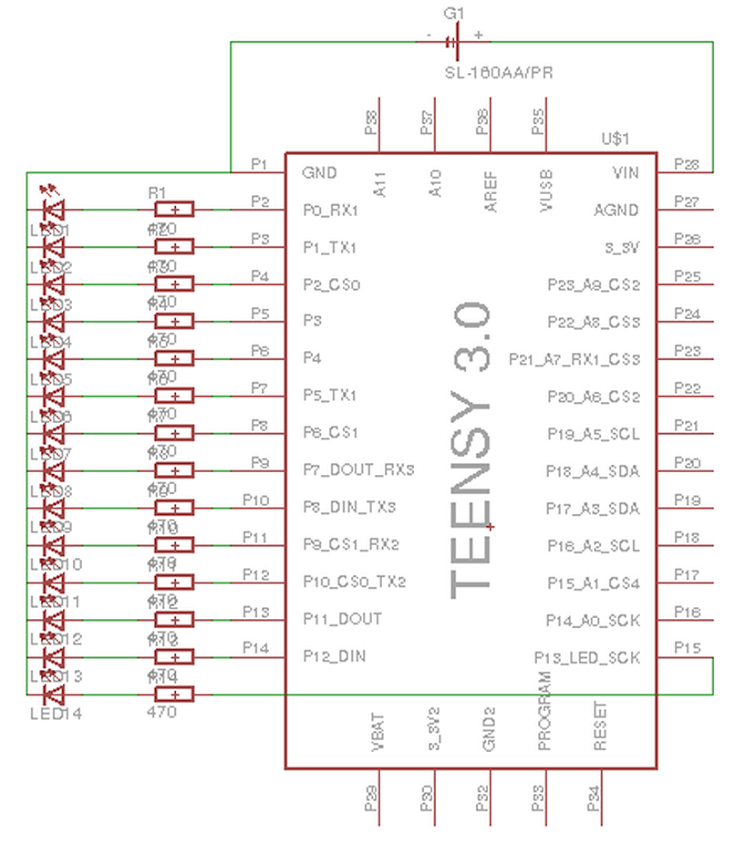

My setup was originally on the Open Access Control 3.0 shield for the arduino mega 2560, this shield has a SN65HVD05 on it’s hardware serial port 3 and has the Rx/Tx pin connected to pin 16. That’s the thing about adapting an RS232 port to RS485, RS232 is full duplex, meaning it can transmit and receive simultaneously, RS485 is half duplex using one pair of wires as a differential twisted pair for both transmit and receive. The twisted pair differential signaling is better for noise immunity, but because of that it takes twice as many wires to run full duplex. The full duplex equivalent of RS485 is RS422, but that’s a less popular standard for a number of reasons. When adapting RS485 to RS232 the adapter chip has a pin to enable receiving RS485 signals to RS232, and another pin to enable driving the RS485 signals from RS232. These pins are usually opposite polarity so that one digital IO can control switching from Tx mode to Rx mode. This particular use of the display only connects to serial port 1.

The following information is just on the features I implemented, some features were not present on the devices I handled, some features I didn’t find useful, and some features I couldn’t figure out, that’s why they weren’t included.

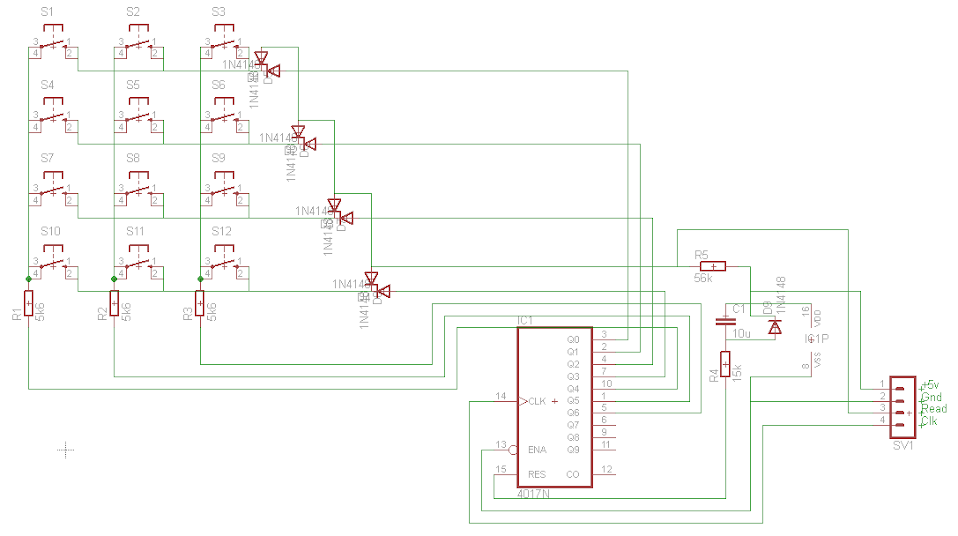

There are two modes I used these displays in: single unit mode, and multi-drop mode. Single unit mode is exactly as you might expect it, one display connected to one serial port taking commands directly. The multi-drop mode adds a packet format to the device as described in the manual I have linked to above and the code I link to down below. In multi-drop mode any number between 1 and 255 can be used as a display address except 4, 4 is the end byte in the message protocol. These codes may seem arbitrary, but they somewhat faithfully implement the ASCII table’s control characters (start of text, end of transmission, etc…). The commands for single unit mode and multi-drop mode are the exact same, except the multi-drop ones are wrapped up in a packet with an address in it.

There are four modes for taking input from these displays, we’ll go over them one at a time.

Buffered/half duplex mode allows the characters to be written to the screen at the current cursor position without host intervention and also placed in a buffer, the UP arrow key backspaces, the DOWN arrow key places the down character in the buffer. The buffer is dumped when the ENTER key is pressed. I don’t like this mode because it alters the display from a known state without telling the host.

Buffered/full duplex does the same thing as buffered/half duplex, except it doesn’t alter the display. I don’t like this mode either because you can’t tell if the UP key is pressed, and in order to know when any key is pressed you have to hit ENTER (this also applies to the buffered/half duplex).

Instant/half duplex allows the characters to be transmitted when they are typed, but also puts them on the display.

Instant/full duplex is my preferred mode, it outputs keys to the serial port when they are typed and also doesn’t display them (like an old school dumb serial terminal).

These displays have all sorts of features, I really like them. One interesting feature is the ability to set any of the functions to any if the available ports (or an internal 800 character buffer). What I mean by this is the available ports (in my case serial ports 1 or 2, the buffer, or a null port) can be mapped to where the display either takes a specific kind of input, or sends a specific kind of output. Those specifics are as follows:

Main input port: takes ASCII, control codes, and escape codes.

Data output port: when the display needs to send data to the host.

Key control port: used to send keys to the host.

Repeater port: parrots out the contents of Main input port, for use with long cable runs

I personally didn’t use the Repeater port, and I had everything else set to serial port 1, but there’s something interesting about the Key control port.

Since the Key control port can be set to an 800 character buffer, it can be used to buffer a lot of key presses, but more importantly the buffer can be polled in multi-drop mode to figure out who sent those key presses since you can’t set what value the number keys return. In instant/full duplex mode with the key control port set to the internal buffer the key presses are stored in a buffer that can be polled by the host (polling each multi-drop device separately so you know where the key presses came from).

The control codes are very striaght-forward, I implemented the following:

0x0C => clears display, sets cursor to home position

0x10 => the text following will be blinking

0x12 => the text following will not be blinking

0x14 => sets the cursor position, although my implementation only allows you to set the line

0x15 => turns cursor on

0x16 =>turns cursor off

By following the examples I have built into the library it could be expanded to allow all the control codes to be used, but I didn’t find the rest useful.

The escape codes are actuated by sending 0x1B followed by a single ASCII character. I assume the escape codes are different from the control codes because the control codes are implementing the unprintable command part of the ASCII table while the escape codes are able to be entered simply by typing the ASCII character for ESC and another ASCII character at the terminal (something an operator could do). The escape codes I implemented are as follows:

0 => resets the display

1 => disables the keypad

2 => enables the keypad

5 => bargraph on a given line (and clears out the rest of the line)

B => read buffer

C => clear buffer

In order to use my code properly the displays need to either be in Single Unit or Multi-Drop mode, the keypad needs to be set to Instant/Full Duplex, the Main Input Port and Data Output port need to be set to a serial port (I used port 1) and the Key Control Port needs to be set to the internal 800 character buffer (4).

The functions I have implemented are pretty easy to understand after my explanation here and a quick glance at my example code and the library itself. The information provided here is for the use of anyone who needs it, if you have any questions feel free to comment. The thing is, these displays are really expensive, I only got to play with one because it was donated to this project, so most people who use these displays are doing so with “Industry Standard” everything, so they don’t need to know how to talk to them with anything a bit more reasonably priced. If you should happen across one of these things though, jump on it. They are easy to talk to (now) and really slick looking.

You can find my code here, the READMEs are at least a bit descriptive, some of the test code is old and doesn’t use the current revision of my libraries (or use them at all). I intend to put up the code for reading buttons very soon (next couple hours) as I only realized the thing about the buffer while writing this.

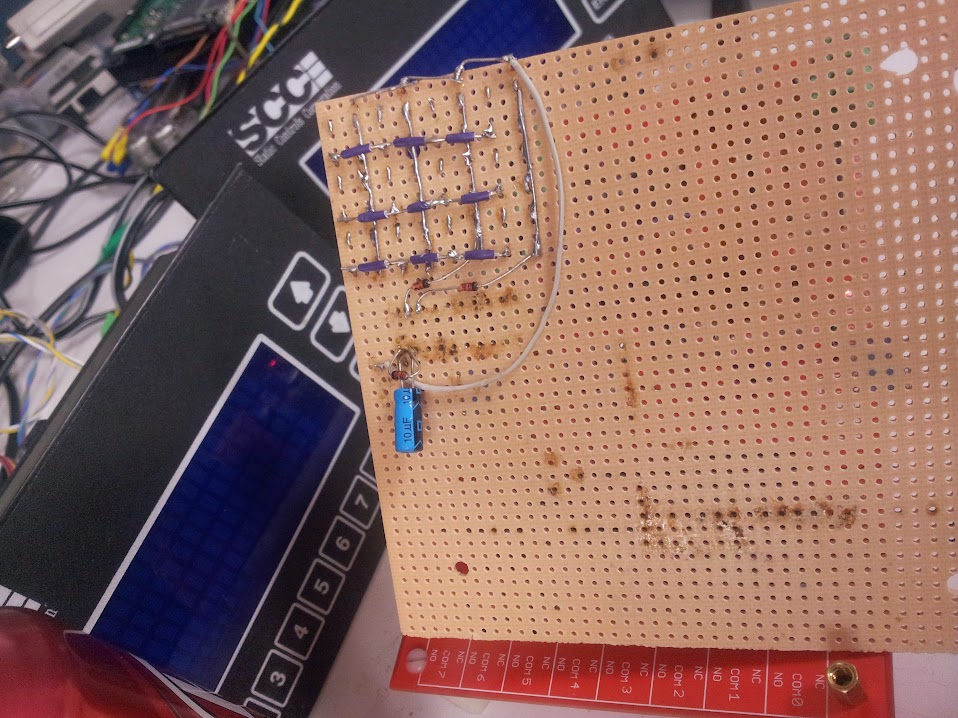

ADDENDUM: I spent a while with this article written as you see above and attempting to get the button reading working from the buffer. I couldn’t do it. I know how it should work (or how I think it should work as the manual I have is different from the firmware on the displays in front of me). I know that once I post this I will get around to trying again and it will work, but for now it’s being posted with the button reading code non-functional (in multi-drop mode, I got instant/full duplex working with the key control port set to the main serial port, but it’s mostly useful if you only have one display so you know which display sent the button). And, of course after I submit this is when I will get around to cleaning up the library. For now common sense would dictate that the higher the number the example sketch, the most updated it is (although I can be counted on to violate common sense at every turn, so take that with a grain of salt).